With the Canadian involvement in the war in Afghanistan being an ever constant reminder of world unrest, it makes it that much more important for us to remember those that served our country during the two World Wars. Soldiers did not have the weaponry, technological advances and communications available to them that the Canadian Forces have today. The threat of discovery by the enemy made it necessary to seek an alternative to traditional radio and telephone communication – giving rise to the role of Motorcycle Dispatch Rider (MDR), or simply, DR.

With the Canadian involvement in the war in Afghanistan being an ever constant reminder of world unrest, it makes it that much more important for us to remember those that served our country during the two World Wars. Soldiers did not have the weaponry, technological advances and communications available to them that the Canadian Forces have today. The threat of discovery by the enemy made it necessary to seek an alternative to traditional radio and telephone communication – giving rise to the role of Motorcycle Dispatch Rider (MDR), or simply, DR.

The position of DR was the only one outside of paratrooper that was voluntary. Duties assigned the dispatch rider varied. For the most part they involved delivering messages to units and headquarters. Those marked “Secret” could by signed for by any clerk. However, those marked “Top Secret” were to be delivered to officers directly – even if that meant riding to the front lines. Messages of importance were also delivered to and from hospitals – how many incoming wounded they could expect, how many discharged, able and fit, reinforcements the lines could expect – soldiers, fresh out of the hospital. Often times the DR had no knowledge about the contents of the message – very seldom were they verbal messages. Occasionally the dispatch rider was called upon to escort supply convoys through unfamiliar territory, relying on the maps they had been given. There were occasions where the maps had no directions, or geographical indication of the roads printed upon them.

For supplies, DRs, if they were lucky, might have carried a couple of cans of beans or beef and maybe a loaf of bread, for sustenance. Their tool kit consisted of a screwdriver, pair of pliers, grease gun and possibly an adjustable wrench. Although instructed not to take unnecessary risks, more often than not riders were expected to deliver the messages in the fastest time possible – riding through unimaginable road conditions. Much of the time, mud was caked so heavy under wheel fenders that navigation became extremely difficult, at best. Sometimes it was just best to remove the front fender. Long stretches of riding time led to sleep deprivation, and ultimately to accidents. Then there was the obvious threat: enemy fire. Yet despite the odds stacked against them, dispatch riders held no rank and were rarely acknowledged for their important role in the war.

At age 19, having completed basic training at Fort William, now known as Thunder Bay, Harry Watts’ official position with the Canadian Armoured Corps initially began as trooper. He arrived at Camp Borden, Ontario, March 1943 and Harry knew one thing: they had scout cars, tanks, wheels, trucks, mud and motorcycles. Watching the tank drivers and mechanics changing tracks in the mud and working on the trucks, then noticing the ease with which the fellows in motorcycle training cleaned up their machines, he decided at that moment he wanted to become a dispatch rider for the Canadian Army.

Trained on a 45 Indian Scout with sidecar, Watts had never ridden a motorcycle before. “I had never even rode a bicycle before that,” the 84 year old laughs. Aside from learning how to ride a motorcycle, Watts also learned how to maintain the machine. “One thing they did at Camp Borden was teach us how to fix and repair them, same thing in England. We took them apart and we had to put them back together as a group to know how they worked. There was quite often a short in the wiring. To find the short, we put a bolt where the fuse was and it would start to smoke where the short was, then we knew where the wire had a problem. If you saw the smoke before it caught fire, you’d fix it and you were away!”

In addition to the Indian, during his years as DR, Watts had ridden Harleys, Ariels and Nortons.

In addition to the Indian, during his years as DR, Watts had ridden Harleys, Ariels and Nortons.

“Through the mountains we might have averaged 30 mph. We would have put on about 200 miles in a day, through switchbacks where you could look down 5 or 6 miles of road.”

“We had to ride through all kinds of weather,” Watts continued. “It was very dangerous. Strictly blackout in England. We moved quick, and without lights. Urgency meant you had to keep going. There were times we needed to get the bike off the road in the case of a tank or truck coming along; or off into a field. We would hunker down at night if it were possible with a bedroll. We had to use our own judgement. If the ground was good, you just unrolled the bedroll. If you had mud, you’d sleep on the bike.”

When asked if he’d ever had any ‘close calls’, reminiscing, he chuckles. “Lots of close calls. Mainly laying down the bike. Just once was I shot at. I heard it [the bullet] go by, it was in November. I knew there were no bees flying around in November so I got down, waited, then took off quick.” According to Watts, the elements [weather] were the real enemy. “The elements made it dangerous, more than physical combat. The enemy was not the big problem compared to the elements. That’s one of the reasons the dispatch rider was killed.”

Watts never needed to fire his arms. “I didn’t carry anything until Italy. Had a Thompson sub machine gun – like you see in the gangster movies. Didn’t carry it much; saw a guy once fall on one and was injured. So I took it apart and put it in my saddlebag. Then my Colonel got me a holster and British Webley 45. Never fired it at anybody. Did a little target practice on lizards, but no people. Never had to make that decision. I considered myself fortunate I never had to do that.”

Reflecting back, Watts added, “Our role was taken for granted. We were called Dumb Roger; Dog Robber; Dumb Russian. Can’t remember any compliments being thrown around.”

Listening to Watts’ chuckles and easy attitude, I felt honoured I was allowed a glimpse into the life of a man whose contribution to WWII gave me what I enjoy today – freedom. The liberty to move freely about; freedom of speech and freedom to fly our national flag – all things, all too often, as the Dispatch Rider, are taken for granted.

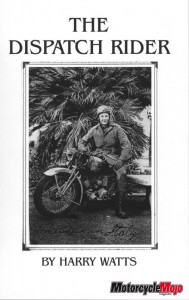

To see what Harry rides today, go to page 72. Read more about Harry Watts’ life as Canadian Army Dispatch rider in his book, “The Dispatch Rider”.