The first time that I ever saw a Velocette Thruxton was at a road race at Harewood Acres, a long-since-gone converted airfield circuit near Delhi, Ontario. The Velo’s owner had parked it in the paddock and wandered off to watch the fairing bashing going on through Gunnery Corner. To me the 500 Velo was pure eye candy.

The Thruxton had the purposeful look of a true road burner, albeit with a decidedly dated looking engine. Sometime earlier I had read a road test on the model in Cycle World, so I knew what I was looking at and what the 500 cc bike was capable of. Little did I know at the time that the Thruxton model would be the most advanced, and also the final version of the high-cam Velocette OHV single.

The history of Velocettes is also the history of a family motorcycling business that would span three generations. The company’s founder, Johannes Gutgemann, was a German immigrant who settled in the Birmingham area in the West Midlands of England. Initially, Gutgemann went by the Anglicized name John Taylor, and by 1904 was building motorcycles in partnership with William Gue. Their bikes were sold as Veloce motorcycles. This early venture failed in 1905, but Taylor went on to form a new company of his own, Veloce Limited.

Taylor had two sons, Percy and Eugene, who were both very capable engineers.

In 1908, the two sons started their own firm, New Veloce Motors, which would build cars, as well as small displacement engines that would power motorcycles built by their father’s firm ,Veloce Limited, located in London.

In 1909, Veloce introduced a 276 cc 4-stroke single of non-conventional design that didn’t sell well. The firm responded by offering a new 499 cc model powered by a more standard design 4-stroke single with belt final drive. This model was a market success and sales began to grow.

In 1911, Veloce launched a small displacement machine that was designed for ladies. Powered by a 206 cc 2-stroke engine, this model was the first to carry the Velocette name. That year Gutgemann took out British citizenship and changed his name yet again, this time to John Goodman.

By 1916, New Veloce Motors had failed, but was absorbed into Veloce Limited as its in-house engine operation. Over the next decade, the Veloce Motor Company introduced a variety of new models using different engines designed by the two brothers. What became evident was that the brothers had quite different design interests. Percy was into high performance and racing models, while Eugene was focused on the design of more basic and utilitarian models meant for mass consumption. This dichotomy of design interests persisted for years at Velocette and taxed the resources of the small firm.

In 1925, Percy Goodman designed an OHC 348 cc sports prototype that was designated as a K model and badged as a Velocette. Three of the new K models were entered in the Isle of Man Junior (350 cc) TT road race, but didn’t do well. The following year a revised KSS model was entered in the Junior TT and it won. Thus began a period of racing works 350 cc OHC Velocette TT singles that would span twenty-five years. Velocettes would win the 350 cc Isle of Man Junior TT again in 1928 and 1929. As a result of those wins, Veloce began selling a new over-the-counter 350 cc racing model, the KTT, that would become hugely popular among privateer racers and would dominate 350 clubman racing for the next decade. The 350 KTTs would win the Isle of Man 350 Junior TT again in both 1938 and 1939.

When postwar road racing resumed in the Isle of Man in 1947, works 350 KTT riders won the 350 Junior TT for three years straight. Not only that, but when the FIM Grand Prix World Championship series resumed in 1949, Velocette won back-to-back 350 GP World Crowns with KTTs ridden by Freddie Frith in 1949 and Bob Foster in 1950. Freddie Frith was an incredible 40-years-of-age when he won his 350 cc World Championship, and promptly retired from racing.

During the twenty-year period, 1930-1950, the Veloce Motor Company designed and built a variety of different motorcycles powered both by 2-stroke and 4-stroke motors. Mainstay models that sold well through the 1930s included the 248 cc MOV (1933), the 349 cc MAC (1934), and the 495 cc MSS (1935). Each of these models incorporated a high-cam, short pushrod layout that became standard on all of the road-going Velocette 4-stroke singles, including the later Thruxton.

Once the war was over, Velocette began reintroducing their road-going OHV single models.

Unlike some larger competing British firms, Veloce had produced few bikes for the war effort, and had to struggle to get back on their feet when peace resumed. Veloce was always a relatively small firm and never employed more than 400 workers. Their machines were much more hand-made than those built by their competition, a factor that contributed to their higher price tags.

If Veloce had focused fully on moving ahead with updated road-going singles in the early postwar years they would likely have recovered their pre-war market strength, but this didn’t happen. They tried to do more than their modest resources could support and suffered for it.

Percy Goodman died in 1951 at which point the Velocette works race shop was closed.

By now brother Eugene had introduced a new model, the LE, for which he predicted large volume sales. The ungainly LE employed a pressed-steel frame and came fitted with running boards and leg shields. It was powered by a 149 cc water-cooled, side-valve, horizontally opposed flat twin with shaft drive. The engine had to be cranked to start and employed a hand gearshift. Not surprisingly the public didn’t go for it, though it did prove popular as a local police bike. Even so, sales were barely one fifth of Eugene’s expected volume. It should have been dropped, but wasn’t.

In 1956, responding to market demand for bigger and better bikes, Veloce introduced two new sports models, the 500 Venom and the 350 Viper. The Venom was capable of 90 mph (145 km/h) and could easily be upgraded for racing use. From 1960 onward both models were also offered as Clubman models with lowered bars, tuned engines and upgraded suspension for high-speed use. The Venom Clubman proved to be a popular model and performed very well in endurance racing.

In March of 1961, the factory took a team to France for an attempt on the 12-Hour and 24-Hour Speed Records for a 500 cc machine. The venue for the attempt was the banked Montlhery circuit outside of Paris. The company’s up-rated 500 Venom Clubman succeeded in setting a 12-Hour Record at 104 mph (167 kph) and a 24-Hour Record at 100.05 mph (161 kph). These results cemented the reputation of the Velocette Venom as a fast and durable machine.

In 1964, the firm introduced a special version of the Venom Clubman with a new cylinder head, narrower valve angle, larger inlet valve, revised intake and a large Amal GP carb that in order to fit necessitated cutting a notch in both the gas tank and the oil tank. The new machine won the 500 class of that year’s gruelling Thruxton 500 mile endurance race giving rise to a new model introduced the following year.

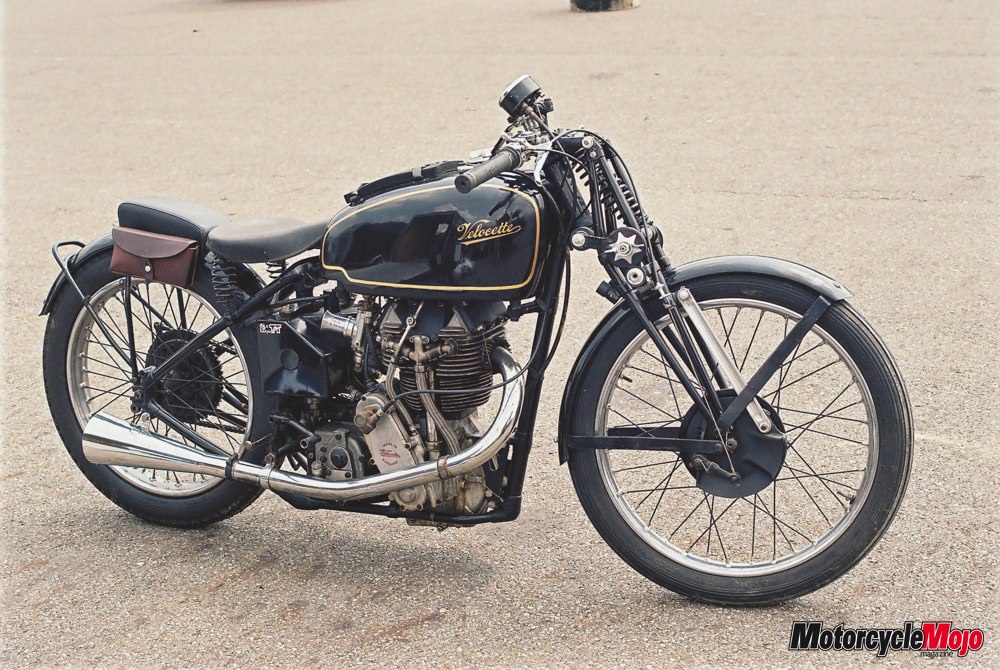

This model was the Velocette Venom Thruxton introduced in 1965, a genuine ton-up café racer for the serious enthusiast. The Thruxton had a new cylinder head based on a squish-type design that had been developed by Lou Branch, Velocette’s U.S. importer. It incorporated a two-inch down draft intake, a larger intake valve, a high performance camshaft and a higher 9.2:1 compression piston. Fitted with a 1 3/8” Amal GP carburetor, the standard bike produced 40-41 bhp at 6,200 rpm, and was good for a top speed of 105-110 mph (169-177 km/h) in stock form.

The Thruxton came with clip-on handlebars, rear-set foot pegs, a humped leather racing type seat and a notched 4.5-gallon fuel tank. Other features of the model included separate stand-up speedo and tachometer, a sweptback header pipe and a traditional Velo fishtail muffler.

The frame employed was a standard Venom dual loop unit with a single front downtube, fitted with upgraded telescopic front forks and dual Girling shocks at the rear. As with other Velos, the angle of the rear shocks could be adjusted to accommodate varying passenger loads by making them more vertical for heavier two-up riding.

The bike ran on 19-inch alloy rims front and back, fitted with a 3.0” x 19 front tire and a 3.5” x 19 rear. Stopping power was provided by a 7.5” (190 mm) diameter double leading-shoe front drum brake with an air scoop and a 7.0” (178 mm) single leading shoe rear brake. The bike had a fairly hefty dry weight of 390 lbs. (177 kg) and a wheelbase of roughly 54 inches (1.37 m).

As with any high performance, large carb single of the day, starting required adherence to a set procedure if trouble was to be avoided. This typically involved tickling the carb (flooding the float chamber), easing the piston over compression with the use of the compression release, setting the throttle opening, and then giving a good non-stiff-leg downward kick on the kick starter. A well set-up bike would usually start with 1-3 kicks.

Being a non-counterbalanced single, vibration was a fact of life with the Velo, but back then most big bikes vibrated. At idle the front wheel would dance a bit, but once underway the vibration was not a problem, and would disappear above 4,500 rpm, which made the bike a comfortable high speed cruiser.

Fitted with standard gearing, the Thruxton would be pulling only 4,000 revs at 70 mph (113 km/h), and could cruise indefinitely in the 80-90 mph (130-145 km/h) range. More than a few British 650 twins of the day found staying with a 500 Thruxton hard going at speeds above 80 mph.

The one clear chink in the Thruxton’s armour was its ability to overrun its headlight in high-speed night riding. The Velocette electrical system was 6-volt which yielded a relatively yellow and weak light output.

The high speed and good handling capabilities of the Thruxton were proven repeatedly in race competition. A Velo Thruxton team won the 500 cc class of the 1965 500 Mile race, run that year at the Castle Combe circuit in Wiltshire, England. Then two years later, a pair of Velocette Thruxtons finished first and second in the 500 cc class of the inaugural Isle of Man Production TT race. Race winner Neil Kelly averaged 89.89 mph (144.7 km/h) for the distance with the fastest lap at over 91 mph (146.5 km/h), while second place finisher Keith Heckles had a race average speed of 89.15 mph (143.5 km/h).

A tweaked production racing Thruxton could produce a further 5 or 6 bhp over stock and, when fitted with a full fairing, could top 120 mph (193 km/h).

Later model Thruxtons were fitted with a concentric type Amal carb, a higher compression piston, and from July 1968 onward had the traditional Velo flywheel magneto system replaced by a battery and coil ignition (still 6-volt) that was reportedly a lot easier to live with.

In early 1969, the British motorcycle weekly Motor Cycle ran a road test using a staff member’s up-dated Thruxton. Two of the things that really struck the testers about the 500 Velo was its tractability and its fuel efficiency, something that they hadn’t expected from a big single fitted with a GP carb.

The testers reported that the Velo had a non-lugging speed of 28 mph (45 km/h) in top gear, and could paddle along all day at 3,000 revs. Fuel economy testing revealed the following remarkable results of 96 mpg at 30 mph, 70 mpg at 50 mph, and 57 mpg at 70 mph. These were the type of fuel economy results than you would typically get with a good 250 cc machine in the late 1960s, not a built-for-speed 500.

Production of the Thruxton continued until late 1970 by which time Veloce was financially on its knees. Far too much money had been spent on the various LE variants which drained cash from the firm, plus other abortive designs. The last of these was an unsuccessful 250 cc 2-stroke, flat-twin scooter called the Viceroy. It was hoped that this model would enable the firm to cash in on the scooter craze.

In the final years of Veloce Limited, two of John Goodman’s grandsons were managers of the firm. After sixty-six years in the motorcycle business the family voluntarily closed the company in February of 1971.

By then the firm had reportedly produced some 1,108 Thruxtons, half of which were exported, with over two-thirds of those coming to North America. Most of the Thruxtons were fitted with a silver and blue pinstriped fuel tank, but from 1967 onward the model could also be specially ordered with a more traditional black with gold pinstripe Velocette tank.

Today a mint 500 Thruxton, fitted with the classic Avon AR 9 bubble-nose full fairing, can fetch a price in the $20,000 – $25,000 range, if not more. Despite this, you don’t often see them coming up for sale.