As one of the brightest jewels in the Barber Museum’s dazzling crown, Britten number seven exudes a semi-mystical presence in the rarified air of this 80,000-square-foot motorcycle shrine. There, amongst hundreds of significant motorcycles and thousands of incredible stories, the Britten stands alone as probably the most evocative embodiment of one man’s dream. Following a path created in his mind to build a world-beating race bike, John Britten took his thoughts, and with every ounce of courage, determination and skill he possessed, turned them into reality with his own hands. Humbling factory race teams on the track with its performance and giving race fans a modern-day David as a champion against the corporate Goliaths, the Britten could possibly be the last true privateer-built race bike we will ever see.

Sadly, only ten of these incredible machines exist, as John Britten lost his life to cancer in September 1995, just months after winning an epic victory on the high banks of the Daytona International Speedway during Bike Week. John Britten achieved his dream of beating the world with his “handmade” motorcycle, and his heroic struggle for victory was permanently consigned to the record books. Thankfully, Mr. Barber realized the significant part John Britten played in the history of motorcycle racing, and Britten number seven now shines brightly in his world of motorcycle brilliance.

Born in Christchurch, New Zealand, in 1950 to Bruce and Margaret Britten, John was a twin to his sister Marguerite and younger brother to his sister Dorenda. Starting his life of building and tuning early with go-karts, by the age of twelve he had figured out how to power them with small engines. A year later he found an old Indian motorcycle, and he and good friend Bruce Garrick began to restore it. The writing was on the wall. A four-year degree in mechanical engineering led John into a career as a cadet draftsman, where he would first be exposed to a variety of processes including mechanical engineering and mold design. This was followed by a stint in Europe before he settled back in New Zealand to work as a design engineer. By 1982, he owned his own business designing and producing handmade glass lighting and was married to his lovely wife, Kersteen. Later, he went to work for her family’s property management and development company, which saw him enjoy great success with a prestigious apartment building project that came to fruition in 1990.

By this time, John Britten had already been hard at work on developing motorcycle designs, and built his first race bike. This was powered by a Ducati Darmah bevel-drive engine and raced in 1985 by a friend, Mike Brosnan. John Britten also built a second bike that he raced himself, and this first style of race bike became known as Aero-D-Zero. Aero-D-One followed, and it hit the track in 1987. This bike was fitted with a Ducati engine that featured Denco four-valve cylinder heads. For this project, John Britten built a composite monocoque chassis with an aluminum swingarm that mounted directly to the engine. Featuring an under-slung White Power shock, White Power forks, AP Lockheed brakes and Marvic wheels, the bike had a heavy Moto GP influence thanks to fellow Christchurch resident and top GP tech, Mike Sinclair.

This first race bike had more than its share of problems, though, with tediously slow access to the unreliable Denco/Ducati power plant due to the monocoque design of the frame. John Britten finally decided to start fresh and build his own bike from the ground up, including his own engine. These first bikes would go on to evolve into the Britten pictured here in the photographs, and would become the machines that have so firmly etched John Britten into the pages of motorcycle history.

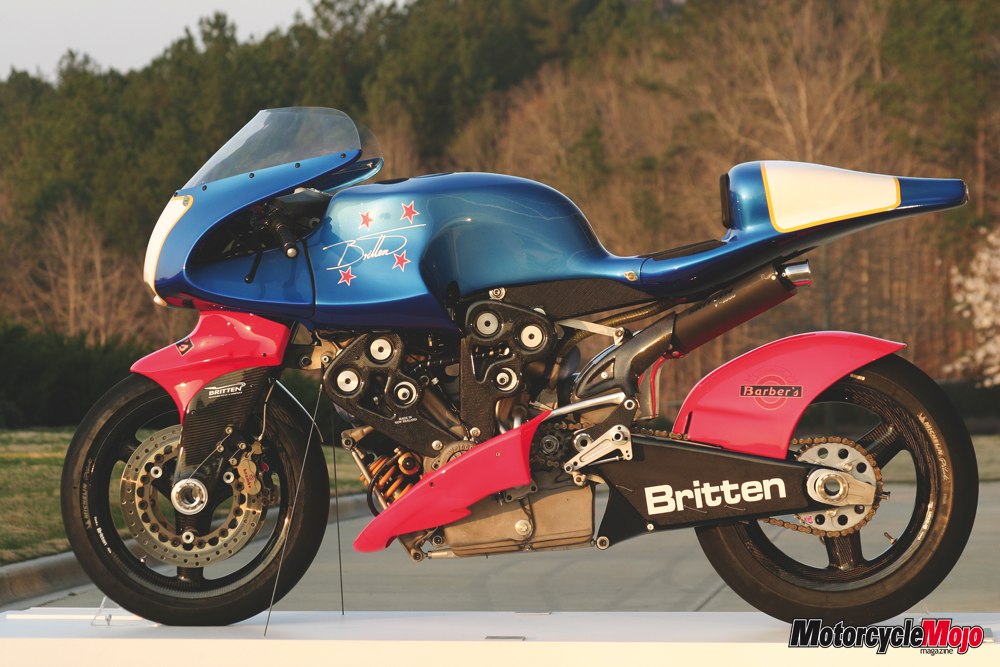

Starting with a wire-frame model, John borrowed technology learned in Formula One racing, sculpting his handmade carbon-fibre bodywork with air ducts that forced air under the bike. This created a down force to push the bike into the racetrack. Always shunning convention, he located a smaller radiator under the seat to take advantage of this airflow, while improving the aerodynamics: the bike now had a much smaller frontal area without the large conventional radiator in front of the engine. Another by-product of the bodywork being produced in carbon fibre was its much lighter weight, which allowed the bike to take further advantage of the horsepower available. The amount of horsepower varies depending on who you are talking to, but it was somewhere in the region of 160, and was produced between 12,000-12,500 rpm.

This healthy dose of power was provided by John Britten’s own V-Twin engine. Casting the first casings in his wife’s kiln, the engine used in the Barber machine displaces 1000 cc, uses four valves per cylinder, and is exquisite in its design and manufacture. With no counterbalancers, gear-driven primary drive, and a dry clutch, it was a loud and violent animal even at idle, and also something of a fragile one. Due to the incredibly high piston speed, the engine needed to be stripped for inspection and possible refurbishment after five hours of continuous running. Dismantling and rebuilding this engine is a very expensive business, and Barber’s Brian Slark told me they found this out the hard way when they raced the bike a few years back. The bike unfortunately dropped a valve seat and destroyed the motor, which necessitated a very extensive and wallet-lightening rebuild.

Talking with Brian about the bike and absorbing his comments about its near-timeless design, even though it is more than fifteen years old, just makes John Britten’s vision and achievements even more incredible. Going head to head with factory race-bikes at Daytona in 1995, the Britten astonished the world by winning the Bears World Championship race, as well as finishing second and third in the Battle of the Twins race. These podium-topping finishes more than proved the validity of his engineering and design, and the bike went on to win four more races in Europe that year.

Incredibly sophisticated in many aspects, the bike used a fuel injection system that could be adjusted by a laptop computer. This was a first in the motorcycle world at that time, and just one more example of Britten’s progressive thinking. His suspension was not only adjustable for rake and trail, but also for dive, and was basically a redesign of the Hossack girder/wishbone parallelogram system, which was itself an update of the original Vincent front suspension. These unique girder forks, the lack of frame, and the wild colours turned heads whenever the Britten would fly the Southern Cross. And there in the pits working round the clock was the enigmatic John Britten, flying in the face of conventionality as he lived his dream to the fullest.

Before his passing, John Britten had a wish that a total of ten Brittens would be produced, and back in New Zealand his dedicated team completed this task after his death. With this handful of rare gems now spread around the world, mostly in private collections, it is fantastic that a trip to the Barber Museum in Alabama affords the pleasure of viewing one of these machines in person. Standing proud in a sea of exotic and storied motorcycles, it is possible to spend as much time as you like letting your eyes wander over the smooth, sumptuous lines, while marveling at some of the 6,000 handmade pieces that form this masterpiece of mechanically functional art – a piece of art that was born in the mind of one man, formed by his own hands, and raced to success on the world’s racetracks. John Britten’s legacy lives on as a reminder that we must never stop dreaming, never stop believing we can make a positive difference in our world, and a reminder that good guys do occasionally finish first. And, in John Britten’s case, some of them get to kick a little ass along the way.