Designed during the Second World War, the Triumph TRW 500 is still a reliable mount for a peaceful country ride.

Over the past hundred years or so, many motorcycle manufacturers have built special models for use by the military, police departments and other government ministries. The original Triumph company was one such concern, building military models during both World Wars, as well for peacetime use.

The TRW 500 side-valve vertical-twin was one of these machines. Typically, such bikes had to be capable of off-road running in various adverse conditions, including the ability to climb relatively steep grades and to traverse a stream with 38 cm (15 in.) of water. Hence, ruggedness of build, durability and reliability were essential attributes of such machines.

So too were simplicity of design, ease of maintenance and repair in the field, and such things as a quiet exhaust, so as not to draw the attention of the enemy or to aid them in locating the source of any noise. Part of the original design specifications for what became the TRW 500 was that it was not to be audible at a distance of 0.8 km (half a mile).

The original design work on the bike was started in 1942 by Bert Hopwood to meet the British military’s need for a side-valve 500 for the war effort. These bikes were meant for use in couriering dispatches, staff car and convoy escort, military police security work, patrolling, reconnaissance and so on. At that time, Triumph was already building a 350 OHV single for the military.

The original design work on the bike was started in 1942 by Bert Hopwood to meet the British military’s need for a side-valve 500 for the war effort. These bikes were meant for use in couriering dispatches, staff car and convoy escort, military police security work, patrolling, reconnaissance and so on. At that time, Triumph was already building a 350 OHV single for the military.

So what really led Triumph to the build their side-valve 500 twin? Some say a huge shouting match between then Triumph-owner Jack Sangster and his chief designer, Edward Turner, who promptly quit, jumped ship and became chief designer at rival firm BSA.

When Sangster heard that Turner was designing a new side-valve 500 BSA twin for a military contract, he immediately ordered Hopwood to do the same thing, and to get it finished before Turner. Hopwood completed the 500 twin by February 1943.

For various reasons, Triumph’s side-valve 500 prototype never made it into wartime production, even though it met all of the required design brief specifications, including a dry weight of just 127 kg (280 lb.)

As it turned out, a modified and updated version of the bike, the TRW 500, was selected for postwar use, with production beginning in 1948 and continuing until 1964. While originally intended primarily for use by the British military, most TRWs were in fact exported, seeing service with the armed forces of many Commonwealth countries worldwide, as well as with various NATO forces. Many were purchased by the Canadian military.

Although the model design was by that time outdated, TRWs remained in military service well into the 1970s before being declared surplus to needs and sold off to the private sector. It was fairly common in the 1960s and 70s to see these bikes, both assembled and still in the crate, being offered for sale for three or four hundred dollars, less than half the price of a new 250 at that time.

There is little question that for a long time, the British military markedly preferred side-valve engines, so-called because their intake and exhaust valves were not located in the cylinder head (as with 4-stroke, overhead-valve engines), but beside the cylinders. Such engines are also often referred to as “flatheads” because there is very little to the cylinder heads that sit on top of the cylinder barrels, including no valve train.

In the case of the TRW, the one-piece cylinder head housed shallow left- and right-side passageways for the twin-cylinder’s fuel/air intake and exhaust emissions, plus two off-centre tapped holes in the head for the sparkplugs, much like the setup on many 2-stroke twins.

The TRW engine valves are located at the front of the engine barrel in vertical pairs. The intake valves are situated inboard and the exhaust valves are located outboard, with waste exhaust gases vented via downward- and outward-sloping exhaust ports.

The fuel/air mix provided by the engine’s solitary 26 mm Solex carburetor passes through a channel between the cylinders to reach the intake valves at the front of the motor, from where access to the cylinder head is upward through the open intake valves.

The TRW engine, because it is a flathead, is short, compact and relatively lightweight. This all contributes to a low centre of gravity, even when mounted in a rigid frame with a fair bit of ground clearance (15.9 cm) for off-road riding.

The TRW came with a decompression valve plus a two-position switch on the carb to assist with cold/cool engine starting. Given the low 6:1 compression of the engine, these bikes, even using the traditional kick-starter mechanism, are easy starters, usually firing on the first or second kick when properly set up.

As was common for its day, the TRW’s dry-sump engine and 4-speed gearbox are independent of each other. The transmission is geared for low-speed pull, and the engine was tuned for torque and tractability rather than top-end performance. Oil for the engine was supplied from a 3.4 L, frame-mounted oil tank positioned at the back of the engine, while the gearbox runs in its own separate oil.

Three versions were produced over the life of the model: the Mks 1, 2 and 3. The main differences involved ongoing improvements to the 6-volt electrical system. The Mk 1 came fitted with a BTH magneto, while the Mk 2 had a battery and alternator setup with a DKXZ distributor and a single ignition coil. The later Mk 3 benefited from twin ignition coils.

The stock TRW chassis employed a steel tube frame with a large single backbone, and one front downtube that connected to two lower cradle tubes to support the engine. In turn, these connected to the rear vertical tube that supported the oil tank, battery, and other items.

The bike’s rear end was rigid with cushioning for the rider coming from an adjustable solo saddle fitted with two large coil springs. Period Triumph telescopic forks kept the front end planted.

Some TRW models also featured a small pad-type passenger seat affixed to the rear fender, though this was a pretty basic setup. The standard height of the solo saddle was 78.7 cm (31 in.). Racks to support a pair of detachable military pannier bags were also a standard item.

The TRWs rolled on 19-inch, steel-rimmed, spoked wheels front and back (WM 2 and WM 3 respectively), both of which were fitted with smallish, seven-inch drum brakes that provided reasonably good stopping power. Standard tire sizes were 3.25-inch on the front and 4.00-inch on the back.

The original military specs set for the machine were meant to enable its riders to deal with a number of riding challenges, as well as to get out of foreseeable problems while under military threat. Thus, the TRWs have a relatively short 135 cm (53 in.) wheelbase, a low centre of gravity, light weight, good manoeuvrability and rider-friendly, low-speed handling. All the better for making a quick about-face and a sharp departure from the scene should circumstances require it.

The fuel tanks on the TRWs are rated at 14 litres and should be good for some 320-plus km per tank under normal street riding in the 80–85 km/h range. While the original 1946 Ministry of Defence spec for the TRW called for a top speed of 112-plus km/h (70-plus mph), and despite the English magazine Motor Cycling reportedly getting 119 km/h (74 mph) out of one in a 1953 road test, around 105 km/h (65 mph) seems to be a more typical top speed.

The TRWs were never meant to be a fast bike with precision handling for a twisty road. They develop about 16 to 17 hp, which is low even for a vintage 500, and have dry weights in the 145–164 kg (320–360 lb.) range. This equates to a bike that will be rider friendly and very satisfying in the role of a leisurely touring bike, as many current TRW owners will attest.

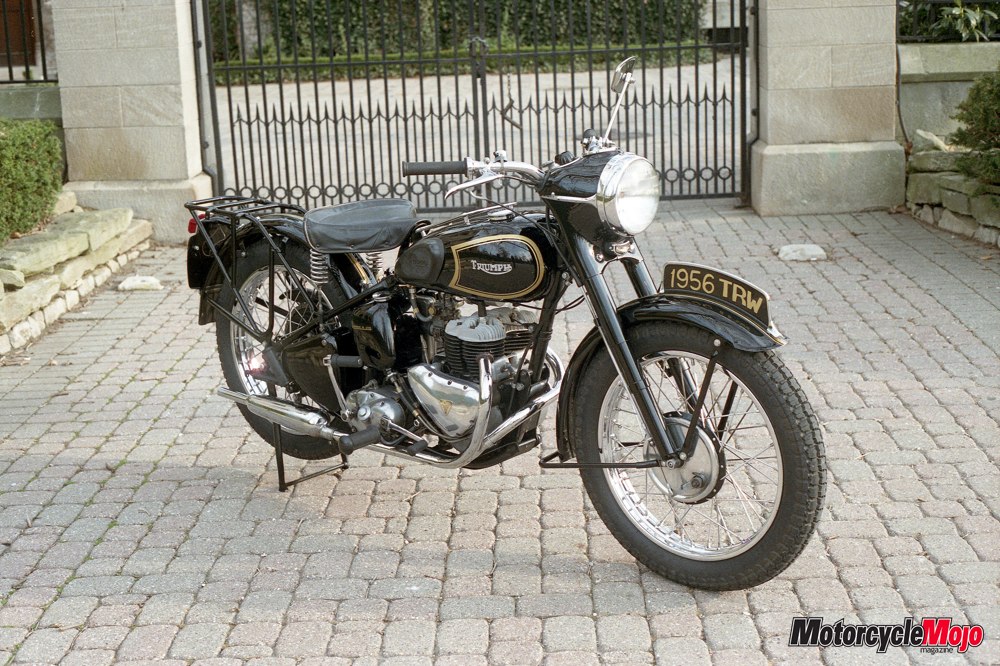

The machine pictured with this article is a 1956 Mk 2 which was a two-year restoration project undertaken by the Hartley family for their daughter Heather as a reward for graduating from university.

Father Tom had originally purchased the bike as a basket case in the early 1970s, then later sold it to a friend as a restoration project that never got off the ground; he reacquired the machine many moons later. After that, the bike sat around in the background waiting for some eventual attention. The idea finally came to restore the bike for Heather to ride.

Fortunately for all concerned, the TRW engine and gearbox had all of the requisite parts and were in reasonably good condition. The same couldn’t be said for much of the rest of the bike. While Hartley had primed the bike early on as a preservative step, the whole machine had to be taken down to the bare metal before the restoration process could begin.

Tom rides a Ducati sportbike, of which he says, “I can count the number of separate painted parts on my Ducati on my fingers. This Triumph, on the other hand, had some sixty-five separate parts that had to be individually stripped and repainted.” The end result, as the photos indicate, was well worth the effort. Heather and her brother, Geoff, both worked on the TRW restoration, with Heather herself doing all of the contrasting gold paintwork.

Virtually all of Heather’s bike is original, right down to the factory wiring harness and the recessed ammeter in the bike’s combination headlight and upper fork tubes nacelle. Better still, everything works like new or better than original, thanks to a number of detailed quality improvements. These included converting the bike to 12-volt electrics and ridding it of its flickering headlight phenomenon, something that Tom attributed to defective wiring grounds.

The fully functioning lighting system even includes the auxiliary, mini front running light required for night riding during the Second World War. It’s the small, cigarette lighter–sized white light located directly below the main headlight. Tom says, “You might have avoided being strafed by a night fighter by using it, but you also would have ridden into a bomb crater before you saw it.”

Heather’s bike starts easily on the first or second kick, idles steadily at low triple-digit revs with no shudder, and yet picks up revs cleanly when the throttle is blipped. What really struck me about her TRW was its mechanical quietness. Absent was any of the mechanical rattle and clatter often associated with later-model vintage OHV Triumph twins. Settings-wise, this bike was tight – it didn’t show a drop of leaking oil.

Long-time friend Dave Rieveley, who also helped with the restoration, made the casual comment while listening to the bike that “the only time you hear an OHV Triumph twin that mechanically quiet is just before it seizes up!”

Heather’s TRW is also pretty quiet when under way, yet emits a good-sounding exhaust note from its standard two-into-one, Siamesed, single-muffler system. The bike moves easily through the one-down and three-up gearbox, though neutral can be tricky to find if you wait until you come to a full stop before snicking it in.

The bike will pull smoothly in fourth from as little as 40 km/h (25 mph), though it’s peppier if you drop it into third before giving it some gas. On the open road, the TRW is a comfortable and predictable runner, one that lets you see and enjoy the countryside that you are rolling through before it’s gone from sight. To a great many bikers, this laid-back sort of experience is a valued and integral part of what owning and riding a motorcycle is all about.