Belt, chain or shaft drive? This month, we’ll review each system. Each has its benefits and drawbacks, and understanding the differences might help you decide when shopping for a new bike.

First, we’ll tackle the drive chain. It’s the most common drive system, helping propel motorcycles for about a hundred years, and bicycles longer than that. Aside from being a reliable and efficient means of transferring power to the rear wheel, the main reason for its longevity in the industry is low cost.

There are several benefits to using chain drive, and one of them is versatility. You can easily and inexpensively change the final drive ratio for better acceleration or more relaxed highway cruising. A chain can also handle all types of conditions, from dry desert heat to being submerged in water during an off-road, trailbike ride, with little fuss. Mud, sand and rocks pose little danger to a drive chain, as long as you look after it.

And therein lies the major drawback of a drive chain – it requires regular maintenance, including lubrication and adjustment, as well as occasional replacement. A chain will also sully the rear of the bike, as all the lube you so tediously apply will eventually work its way onto the wheel, swingarm and even rear fender. And drive chains are noisy – just pull in the clutch on your chain-driven bike and coast at speed for a while, and you’ll see what I mean.

And therein lies the major drawback of a drive chain – it requires regular maintenance, including lubrication and adjustment, as well as occasional replacement. A chain will also sully the rear of the bike, as all the lube you so tediously apply will eventually work its way onto the wheel, swingarm and even rear fender. And drive chains are noisy – just pull in the clutch on your chain-driven bike and coast at speed for a while, and you’ll see what I mean.

Replacement costs, even factoring in the cost of new sprockets, are relatively cheap, especially when you consider that a well-maintained chain can last several years and many thousands of kilometres. However, a poorly maintained drive chain can break and cause serious damage to engine cases, requiring very expensive repairs.

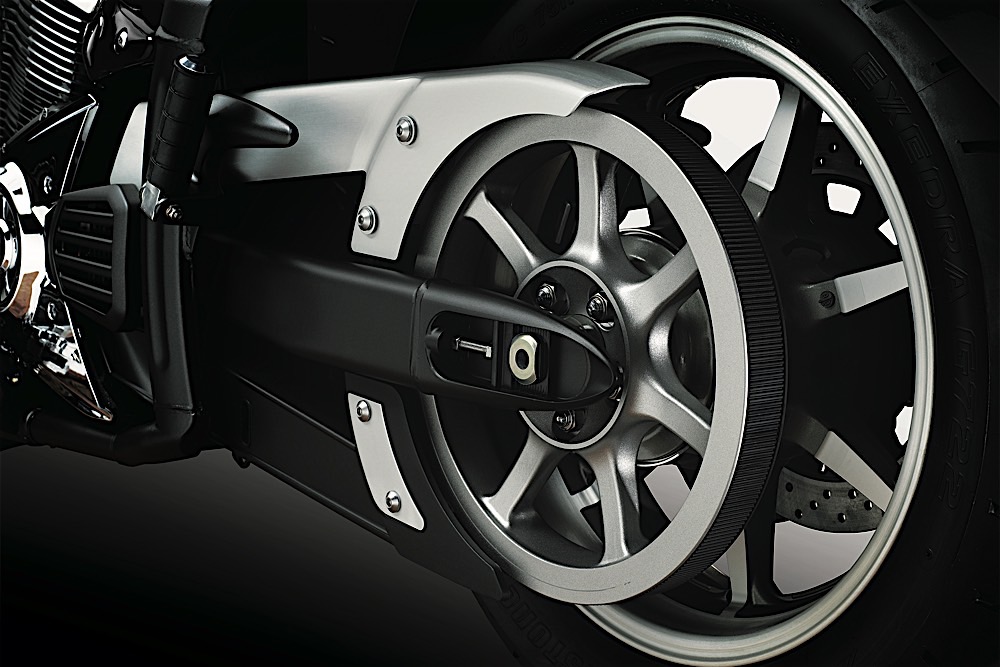

An improvement over a drive chain, in many respects, is a drive belt. It’s actually been around longer than the chain in motorcycle applications – the first motorized two-wheelers were driven by a leather strap. A modern drive belt works on the same principles as a chain, although instead of having links that engage teeth on sprockets to drive the rear wheel, it uses a toothed belt to engage notches on large pulleys.

A belt requires much less maintenance than a chain; you need not lubricate it, and tension is basically set any time the rear wheel is removed – like when changing a tire – and then remains untouched. It is quieter than a chain, and the lack of lubrication means it’s also cleaner. It can also last a very long time – under the right conditions, for the life of the bike.

However, a belt has certain weaknesses, and one of them is that it does not like dirt, and it has an especially acute hatred of mud. This can limit your options if you plan a long-distance tour on gravel roads. A rock thrown up by the rear tire can get lodged between the belt and pulley, and if the rock is large enough, it can snap the belt (I’ve seen it happen). If you encounter muddy conditions, the kind you might find on your way to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, so much mud can get packed between the belt and pulleys that it can put undue stress on transmission bearings and seals, causing them to fail. If you do have the misfortune to break a belt, a replacement will not likely be available at the nearest bike shop, and it will cost about three times the price of a good-quality chain. Even if you carry a spare, replacing a belt usually entails removing the swingarm from the bike, a job not easily performed by the side of the road. Gear ratio changes are also limited, if any.

However, a belt has certain weaknesses, and one of them is that it does not like dirt, and it has an especially acute hatred of mud. This can limit your options if you plan a long-distance tour on gravel roads. A rock thrown up by the rear tire can get lodged between the belt and pulley, and if the rock is large enough, it can snap the belt (I’ve seen it happen). If you encounter muddy conditions, the kind you might find on your way to Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, so much mud can get packed between the belt and pulleys that it can put undue stress on transmission bearings and seals, causing them to fail. If you do have the misfortune to break a belt, a replacement will not likely be available at the nearest bike shop, and it will cost about three times the price of a good-quality chain. Even if you carry a spare, replacing a belt usually entails removing the swingarm from the bike, a job not easily performed by the side of the road. Gear ratio changes are also limited, if any.

Finally, there’s shaft drive. You’d think it’s the most modern of drive systems, but shaft-driven motorcycles have been around since the early 1900s. Unlike chain or belt drive systems, it uses a pinion gear on the end of a shaft to drive a crown gear attached to the rear wheel. This has a very different effect on the rear suspension than a chain or belt, as the pinion gear tries to “ride up” the crown gear. On older shaft-driven bikes, this jacks the rear end up when accelerating and squats it down when decelerating. Newer bikes have altered suspension geometry, or they may use a system of links and extra pivot points in the swingarm to negate this effect.

There are many benefits to a shaft, including less need for maintenance than even a belt, and absolutely no adjustment requirements. All you have to do is check the oil level occasionally (very rarely, in fact, if there are no leaks), and maybe change it once in a while, though that depends on where you ride – deep-water crossings, the type you might encounter when riding off road, might introduce water into the drive unit through the breather, and it will eventually need to be flushed out. Rear wheel removal is also a snap, since there’s no belt or chain that needs to be wrapped around a sprocket or pulley, a procedure that often requires extra hands.

But not all is good with a shaft drive. Shaft drive is expensive to produce, and it adds un-sprung weight, which has a detrimental effect on suspension compliance. And if you don’t notice an oil leak and the drive unit dries out, it will eventually fail, leading to costly repairs. In extreme cases, it can also seize up, which can cause a crash. And if you want to alter the final drive ratio, you’re out of luck.

These different motorcycle final drive systems each have their strengths and weaknesses, but regardless of which one is on your bike, have a good look at it and give it some thought; it might help you better plan your next trip.

Technical articles are written purely as reference only and your motorcycle may require different procedures. You should be mechanically inclined to carry out your own maintenance and we recommend you contact your mechanic prior to performing any type of work on your bike.