Even in the bitter cold of winter, the motorcycle missionary was completely dedicated to helping those of Canada’s northern regions

NWT Archives/Henry Busse fonds/N-1979-052: 5180

Northern LIfe Museum and Cultural Centre

Many Canadian motorcycle enthusiasts likely feel they’re pretty hard done by when it comes to dealing with our northern winter weather conditions. In many parts of this country, as early as October snow inevitably falls, effectively halting any powered two-wheeled activity until the roads are clear again in the spring. There are hard-core riders who attempt to stay in the saddle for as long as possible, many notching up cruises every month of the year. But compared to Father Francis Ebner, the “motorcycle missionary” of the Northwest Territories, those hard-core motorcyclists could be considered fair-weather riders.

Ebner was born January 2, 1918, in Nickerson, Minnesota, in a railroad station while outside, a blizzard raged. According to an essay he wrote that appeared in the book Yellowknife: An Illustrated History, and edited by Susan Jackson, he grew up in Nickerson, then moved with his family to Superior, Wisconsin, when he was 14 and a half years old. First wanting to become a pilot, Ebner was in his last year of high school when the seminary beckoned, and he registered for training near Fond du Lac, Wis.

Moved to NWT

Ebner stayed in Fort Norman for seven months, then moved to Kugluktuk. By 1947, he’d relocated to Yellowknife.

BSA to a Harley

In the same essay noted earlier, Ebner writes: “In 1949 Father Gathy purchased a 125 cc BSA motorcycle for use at the Yellowknife Mission. I rode that motorcycle for three years and in 1952 I was hit by the oil tanker. That same year I picked up a Harley-Davidson 125 cc at the Milwaukee factory.”

Ebner used the motorcycles year-round, travelling hundreds of kilometres between many of the various settlements. He wore a fur-trimmed parka and mittens, and rode even when it was as cold as -43 C.

He writes: “I rode on the snow footpath across the bay from old town to Giant; on the dog trail to the Indian village down the centre of Latham Island. One time I partially broke through the ice on my way to visit the Signals across Yellowknife Bay at their transmitter. I should have known better.”

Interestingly, both of his earliest motorcycles were 125 cc single-cylinder two-strokes. And, both the BSA, which would have been a Bantam model, and the Harley-Davidson were based on a 125 cc design first developed before the Second World War by the German DKW company. In 1945, the design was given to Harley, BSA and other Allied motorcycle manufacturers as part of war reparations. If Ebner had waited until 1953 to get the small-capacity Harley-Davidson, he would have received the Model 165 – same basic engine, but slightly enlarged.

Bigger and Better Wheels

Ebner continues in his essay: “In 1957 I had the K shipped to Edmonton by air, and I rode from that city to Superior, Wisconsin, straight through in 26 hours, stopping only in Regina for mass and breakfast.”

Ebner’s friend Ray Currie, who still lives in Fort Smith, NWT, remembers the priest as being “crazy for his motorcycles.” An article in the December 2, 2013, edition of the Western Catholic Reporter quotes a Father Dennis Croteau, and in it, Croteau states that it was Ebner’s dad who had bought the machines for his son.

Another story suggests it was a wealthy friend of Ebner’s who offered to buy him motorcycles, but there’s nothing to corroborate either version.

Can’t Keep a Good Man Down

Currie always remembers one story in particular that Ebner told him, about what happened when he was returning to Yellowknife: “Somewhere in Saskatchewan a car pulled out in front of him and he hit the car broadside,” he recalls. “Father went over the car and flew more than 100 feet, and broke his back in three places. He recovered and got right back on a motorcycle.”

Trade-up to a Sportster

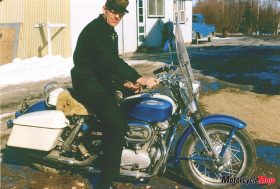

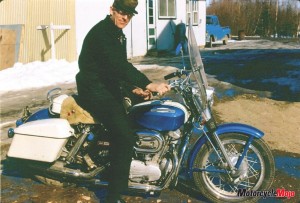

In 1961, Ebner rode the Harley K model south to Milwaukee and traded it in on an XL 883, this one a black and chrome Sportster model. Although not noted in his story in Jackson’s book, Ebner owned other Sportsters after the 1961 model. In an undated photograph, he’s sitting astride a circa 1967 Harley-Davidson XLH, a Sportster model equipped with electric and a kick-starter, hard saddlebags and a windshield.

“There were no paved roads when he was buzzing around Yellowknife and the other communities where he was a busy parish priest,” Currie notes. “In the summer it was gravel, and in the winter it was snow and ice.”

Currie does remind us that the NWT, during the summer months, can be hotter than Hawaii. In mid-June, many of the communities see 24 hours of sunlight. He says, “It’s no worse than Edmonton, Alberta. Here, it’s hot in the summer and cold in the winter.”

Ebner was, according to Currie, something of a shy man, adding, “He was also a bit of a loner, but he was involved in the community in so many different ways.”

A Priest and an Engineer

Ebner helped establish St. Patrick’s Catholic School in 1952 in Yellowknife – the first Catholic school in the community. As part of his role in the school, he became a Third Class Steam Engineer and oversaw St. Patrick’s boiler system.

According to a Northern News Services article written by Jorge Barrera, published on February 28, 2001, Ebner lived for six years in the basement of the school, “with an ale box as a typewriting stand, a small cot and a wash sink as furniture. He’d get up at 5:30 a.m. to celebrate mass and then head to work as the caretaker of the school.” When Ebner eventually moved to Hay River in 1967, he paid similar attention to the school in that community, as he became a general custodian, completing much of the maintenance chores.

Historically Important Artifacts

In 1974, Ebner moved to Fort Smith, where he was a curator of the Northern Life Museum, a facility that held some 12,000 artifacts, many of them collected over the years by Ebner himself. By 1985, he resided in Inuvik, but retired in 1992 to St. Albert, Alta, where he again worked in a museum. He died in that community on November 17, 2013. Father Francis Ebner lived to 95.

Benjamin Lyle Berger, who at the time was a research associate at the Provincial Museum of Alberta, says he asked Ebner why he rode a Harley-Davidson in the NWT for more than 20 years, and especially in the winter.

The priest always simply replied, “It was a good horse.”