If you plan to restore a motorcycle, it’s always best to find a project in reasonable condition, and have lots of patience.

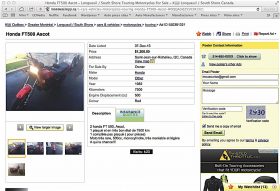

There are several reasons to restore an old motorcycle, all of them valid. You might want to restore a bike to resell it, or maybe to add to a collection. Maybe it’s a valuable collectible, or it holds sentimental value. The restoration of my 1982 Honda FT500 Ascot falls into the last category, as it certainly is not a collectible. It – or more accurately, one just like it – was the first street motorcycle I ever bought, so when I saw a pair of them for sale in an online classified ad two years ago, I bought both for a measly $1,200.

Restoring a bike takes research, a certain level of dedication, patience and, of course, money, ideally the least amount possible. Unless it’s an extremely rare bike, it’s always easier to begin with one that is mostly complete, and when it comes to buying an old bike to restore, remember, it’s all about condition. If it’s a more common motorcycle, a good starting point is to look for one that still has the stock exhaust system and it’s intact. I’ve found that when the bike still has its original exhaust system, it will generally be in good condition. Also note that vintage OEM exhaust systems are very hard to find and rather costly.

Restoring a bike takes research, a certain level of dedication, patience and, of course, money, ideally the least amount possible. Unless it’s an extremely rare bike, it’s always easier to begin with one that is mostly complete, and when it comes to buying an old bike to restore, remember, it’s all about condition. If it’s a more common motorcycle, a good starting point is to look for one that still has the stock exhaust system and it’s intact. I’ve found that when the bike still has its original exhaust system, it will generally be in good condition. Also note that vintage OEM exhaust systems are very hard to find and rather costly.

When I had bought my bike new in the summer of ’82, the first thing I did was strip it of (what I considered to be) unnecessary brackets, change the handlebar, hack things off, trim fenders, swap out the exhaust system (no foresight on my part on that one) and basically personalized it. Ironically, more than three decades later, my goal was to get the FT into as close to original condition as possible.

I had two bikes to work with – one complete and running, the other mostly complete with a defective gearbox – so it was easy to choose which one I’d restore, and which one I’d repair and eventually sell. Fortunately, the good bike had surprisingly low mileage (about 8,000 km), and was complete and original except for the mirrors and levers, and the side covers had small notches cut into them to allow installation of a since removed luggage rack; all the original cable ties were still in place. The biggest issue with the bike was the original paint, which was faded and scratched, and I later discovered that the fuel tank was unusable thanks to interior corrosion.

I had two bikes to work with – one complete and running, the other mostly complete with a defective gearbox – so it was easy to choose which one I’d restore, and which one I’d repair and eventually sell. Fortunately, the good bike had surprisingly low mileage (about 8,000 km), and was complete and original except for the mirrors and levers, and the side covers had small notches cut into them to allow installation of a since removed luggage rack; all the original cable ties were still in place. The biggest issue with the bike was the original paint, which was faded and scratched, and I later discovered that the fuel tank was unusable thanks to interior corrosion.

A good source for parts is eBay, but you must be patient and shop carefully. Check the seller’s feedback rating, and factor in the shipping cost and any exchange rate. Patience paid off for me, as I found OEM mirrors for $55, a fuel tank for $180 and a pair of side covers (one of which still had the owner’s manual pouch attached) for $70, all in excellent shape, though it took several months of searching. I even sourced a pair of OEM handgrips, since they have long been discontinued.

I’ve seen many restorations on which modern tires have been installed, and although this probably gives the bike excellent handling, it just doesn’t look right. The Ascot came equipped originally with either Yokohama, Bridgestone or Dunlop tires. Yokohama no longer makes motorcycle tires, and Bridgestone no longer makes a similar model. Dunlop, however, made the F11 front until a couple of years ago, which I sourced on eBay, and although the original K127 rear has been discontinued for years, the company still produces a period-correct K81 in the right size.

Of course, no restoration is complete unless the bike is mechanically sound, so one of the first things you should do is get your hands on a service manual. The easiest way to get one is to search online. Just enter the year, make and model into the search bar, followed by the term “manual” or “PDF.” You’ll likely get several hits to files you can download. I found a scanned factory manual for the Ascot, for free. The owner’s manual has been a bit more elusive, and I’m still searching for a printed version.

All of the regular maintenance items – brake pads, filters, spark plugs – are readily available through regular parts channels, either through online shopping (I got most of my stuff, including the rear Dunlop, from fortnine.ca) or through motorcycle shops.

The final touch on my bike was a paint job. OEM decals were non-existent, so I got some reproductions from London, Ontario’s Diablo Cycle (diablocycle.com), and the parts went to Tas Custom (tascustom.com) for a new coat. The paint cost the most, at $800, but the bike now looks as good as it did when it left the factory. I even found an original toolkit, which cost nothing. The only item I’m looking to replace now is the scuffed muffler. But I’m patient.

Technical articles are written purely as reference only and your motorcycle may require different procedures. You should be mechanically inclined to carry out your own maintenance and we recommend you contact your mechanic prior to performing any type of work on your bike.