From stolen rides on her brother’s bike to winning a motorcycle GP while competing against some of the greatest names from motorcycling’s “golden era,” Michelle Duff has experienced something very few people have ever done

Illicit rides in the early 1950s aboard a 250 cc BSA motorcycle paved the way for a life-long association with speed and two-wheel power. Michelle (formerly Mike) Duff’s first forays on a motorcycle were taken aboard her brother’s 1949 BSA without permission. From the rather staid BSA, Duff went on to campaign some of the most technologically advanced racing machines built during the “golden era” of motorcycling – the years between 1960 and 1969. For Duff’s involvement in the heyday of motorcycling and helping put Canada on the racing map, she is this month’s legend from Ontario.

“When my brother, Stuart, was in high school, he was friends with a group of about six kids,” Duff says. “One of them had bought an old Levis motorcycle that was often at my parents’ house, and it simply fascinated me. I was still in Grade 7 at that time, and that’s when Stuart bought his BSA.”

Duff, who was born in 1939, rode on the back of Stuart’s motorcycle and quickly grew to understand the concepts of the starting ritual. At 13, Duff began sneaking the BSA out of the garage for rides.

A Natural Born Rider

Duff was grounded for four weeks, and the BSA was to be sold in the spring. However, Duff talked her parents into letting her work on the machine over the winter – ostensibly to ready it for sale. When spring arrived, the BSA did not find a new owner; instead, Duff was allowed to make short rides on the four-stroke single-

cylinder machine.

Rapidly progressing to a larger motorcycle, Duff bought a 1949 Triumph 500 cc Speed Twin. The machine needed a complete overhaul, and her dad thought the rebuild would take at least six months.

“My dad worked for Remington Rand, and he would design and invent things,” Duff says. “We had a fairly well-equipped workshop filled with boxes and boxes of junk I’d toy with, and some of my mechanical dexterity was likely a result of playing with Meccano when I was younger.”

True Mechanical Aptitude

Delivering the Toronto Star newspaper provided the funds to purchase a 1949 Triumph T100 Tiger project. The Tiger came in five individual boxes, and while it still had its iron cylinder and barrel, there was some speed equipment, including higher-profile cams and a dual carburetor setup. Although equipped with a rigid frame, the Triumph had a “sprung hub,” a device that offered a small measure of rear suspension.

“My dad thought it would take me about a year to put it together, but I had it running in two months,” Duff says. “I was 15, and convinced my parents I should go racing with it – and I did.”

In 1955, on makeshift airport tracks, Duff raced as a Junior rider before progressing to Senior status in 1956. The following year, to improve the chances of success, Duff bought a new Norton 500 Manx single-cylinder racing motorcycle and continued to campaign on Canadian circuits, becoming an Expert in 1958.

Off to Europe

Duff’s descriptive writing in her book Make Haste Slowly provides a behind-the-handlebars perspective of many of the European tracks she encountered. That includes her 1960 introduction to the World Championship with a race in the Isle of Man Senior TT.

Duff went on to ride for Tom Arter, an English farm equipment and motorcycle dealer with a penchant for racing. She campaigned mainly AJS and Matchless motorcycles maintained by Arter. With a definite sense of loyalty, when Duff was offered an opportunity to ride Gilera four-cylinder race machines in 1963, she chose not to out of respect for Arter.

But Duff did ride other machines, including Bultacos, MZs and, most notably, Yamahas. In 1964, aboard the Japanese-made twin-cylinder RD56, Duff set the 250 cc lap record and won the Belgian Grand Prix at Spa. Duff says the technological development instigated by the Japanese motorcycle factories in the 1960s made the decade highly interesting.

“Honda first appeared with a 125 cc twin at the Isle of Man in 1959,” Duff says. “In three or four years, Honda was winning just about everything. It was really fast-paced and a time of incredible development.”

AJS Porcupine

Duff raced for Yamaha, but also continued to campaign Arter-prepared AJSs, including a historic model dubbed “the Porcupine.” Drawn during the Second World War by AJS designer Vic Webb and first developed post-war as the E90, the engine was a double overhead cam with twin cylinders canted forward in a near-horizontal plane. Distinctive spiky cylinder head fins intended to aid in engine cooling led the motorcycle press of the day to call the machine the Porcupine. Many of the motorcycle’s components were cast in magnesium, helping to make the E90 a lightweight racer. The bike was supposed to also have a supercharger fitted above the gearbox, but it never appeared, thanks to a ban on the practice as dictated by the FIM racing authority.

With further development, AJS racer Leslie Graham clinched two GP wins and, in 1949, the first 500 cc World Championship using the E90. In 1952, the machine underwent changes that saw the cylinders inclined to a 45-degree angle, and the model became the E95. Although it was no longer fitted with the unusually finned cylinder head, the Porcupine moniker stuck. To lower the centre of gravity, a large pannier-style tank went on the frame in 1954. Only four E95 racers were built, and the machines were capable of making 54 hp at 7,500 rpm. By the end of 1954, AJS pulled out of factory-involved racing and the E95s were quite simply forgotten.

However, in 1964, while visiting the AJS factory, Duff spotted one of the E95 racers leaning against a fence in the yard.

Neglected but Not Forgotten

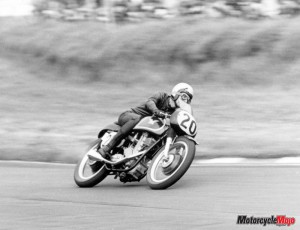

They took the E95 to Brands Hatch for a few laps, where an eagle-eyed photographer captured Duff and the machine on the track.

“The next day in Motor Cycle News there was a photo of me riding it, and that evening we got a call from the factory; they were unhappy with us, but Tom managed to talk them into selling him the motorcycle plus a spare engine and parts.”

The E95 showed promise, but a decision was made to stop racing the machine out of consideration for its rarity and an obvious lack of replacement parts should anything break beyond repair.

An Expensive Competitor

“The joy of riding it was due to its antiquity,” Duff says, and adds, “The Porc was incredibly fast, about midway between the best Brit singles and Hailwood’s 500 MV-4. We could not put a high enough gear ratio on it to prevent it from over-revving on fast racecourses like the Isle of Man TT or Spa-Francorchamps. It was a blast to ride, but we stopped because it was simply too valuable.”

Indeed, in 2000, the Arter/Duff-prepared E95 sold at Bonhams auction in England, fetching approximately US$258,500. That amount was then a world record for a British motorcycle sold at auction, and it now resides in the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum in Alabama.

A Career Stalled

Duff’s racing career took a turn in 1966 when she was testing a Yamaha at the Suzuka Circuit track in Japan. A spill left the racer severely injured with a broken pelvis. Surgeons installed a steel cup to replace a broken hip socket. Duff returned to GP racing the next year, but says of that time, “I was racing on adrenaline, and went back just to get it out of my system.”

By the end of 1967, Duff’s accomplishments included 47 Grands Prix. She stood in top-three finishes in half of those competitions. A short list of achievements includes a third-place finish in 1964 in the World Championship in the 350 Class riding a privately entered AJS 7R. In 1965, she won the 125 Dutch TT at Assen and the 250 cc Finnish GP at Imatra. For Duff, 1965 was a good year; she also had a second-place finish in the 250 cc World Championship aboard the Yamaha RD56. Furthermore, Duff was the first North American to win a motorcycle GP and the only Canadian ever to do so.

By1969, Duff had officially retired from racing. She went to work for Cycle World magazine testing new machines, but by 1972 was set up with a Yamaha dealership in Brampton, Ont.

A Life Change

That’s when Duff, in 1984, set up housekeeping as a woman, and Mike soon thereafter became Michelle.

Duff dropped motorcycles altogether from 1984 to 1990, but a chance encounter at a motorcycle rally near Haliburton and Muskoka saw her back on a machine, and enjoying every minute of it. In 1991, she bought a Yamaha FZR 600.

“I fell in love with it, and it has 130,000 km on it now,” Duff says.

Back on the Track

Duff returned to the European circuits in 1998, when Ferry Brouwer, then managing director of Arai Helmet Europe, invited her over to attend the Centennial Classic TT and ride a lap of honour aboard a specially prepared Yamaha RD56 250. Several more of these kinds of events followed, but a tumble in 2008 left Duff with a serious head injury.

“My doctors advised me not to hit my head again, and it seemed prudent advice,” she says. Duff will still ride, but the Yamaha FZR 600 is currently laid up. “The heads and the barrels should come off for inspection and the crank also checked, but I’m not set up to attempt that work right now.”

Canadian Hall of Fame

A legend in her own time, Duff was inducted into the Canadian Motorcycle Hall of Fame in 2007 for her years of racing against greats such as Mike Hailwood, Giacomo Agostini, Jim Redman, Phil Read and Bill Ivy. She has certainly led a life of motorcycling distinction, and it all began with stolen rides on her brother’s BSA.

Duff’s personal story and racing history is incredibly well documented in her self-published book Make Haste Slowly: The Mike Duff Story. First published in 1999, a second edition was released in 2011. Well worth the $24.95 investment, copies are still available from the Motorcycle Mojo online bookstore.

In Canada, for a book to be considered a bestseller, some 5,000 copies need to be sold. Duff’s first edition sold 3,000 copies, and the second edition a little less – but, given the genre of motorcycle writing, we figure she can add bestselling author to her long list of accomplishments.