Triumph ups its game in the big-bore adventure-touring forum, and its competitors should be wary.

Let’s face it: big-bore adventure bikes rarely get ridden off road, not hard anyway. For the most part, the toughest terrain such bikes will see is gravel, and that’s fine. Sure, there’s a small percentage of riders who will take their BMW R1250GS, KTM 1290 Super Adventure or Yamaha Super Ténéré on challenging off-road rides, or even wander onto some single track — and, with the right skillset, those bikes can do remarkable things on dirt. But their size and weight still make them a handful. You can always opt for a middleweight, like the F850GS, 890 Adventure or Ténéré 700, which can handle deep-wood excursions almost like a true dual-sport. But then you’d be making a compromise in long-distance comfort and convenience if the majority of your trips include loading up the bike or carrying a passenger when hitting the pavement.

Triumph seems to have hit the sweet spot with the redesigned 2023 Tiger 1200, producing a big adventure bike that has tons of power and space for two-up touring, yet is almost as manageable off-road as a middleweight machine. There are five models to choose from (see sidebar), split into two families: the road-oriented Tiger 1200 GT (base GT, Pro and Explorer) and the off-road-oriented Tiger 1200 Rally (Pro and Explorer). Among other differences, the GTs have cast 19-and 18-inch wheels, while the Rally models get tubeless spoked 21- and 18-inch wheels. The Tiger 1200 Rally is unique in that it is the only adventure bike on the market with a shaft drive and a 21/18-inch wheel combo.

A New Engine and Frame

The Tiger 1200 gets a revised inline-triple with a new displacement. While the new engine shares the same bore and stroke as the latest Speed Triple (90 x 60.7 mm), and now displaces the same 1,160 cc (down from 1,215 cc), it is not the same engine. The big difference is a new firing order, derived from what Triumph calls a T-plane crankshaft.

The Tiger 1200 gets a revised inline-triple with a new displacement. While the new engine shares the same bore and stroke as the latest Speed Triple (90 x 60.7 mm), and now displaces the same 1,160 cc (down from 1,215 cc), it is not the same engine. The big difference is a new firing order, derived from what Triumph calls a T-plane crankshaft.

Introduced in the Tiger 900, its crankpins are spaced unevenly, at 180-270-270 degrees, versus the conventional 120-120-120 degrees of the Speed Triple and the previous Tiger 1200. This gives the new Tiger a distinct V-twin-like rumble, and boosts bottom-end power while maintaining power through the midrange and top end. Compression ratio has been bumped to 13.2:1 from 11.0:1, yet the bike still requires only regular fuel. It also makes a bit more power than the previous Tiger 1200, at 148 hp and 96 ft-lb of torque, up from 139 hp and 90 ft-lb.

A new, lighter frame now has a removable aluminum subframe — replaceable if damaged in a crash — as opposed to the previous model’s

welded-on subframe. Steering geometry is a little more aggressive on the GT and, since its engine doesn’t need to clear a 21-inch front wheel as it does on the Rally, it is tilted slightly forward for a more upfront weight bias.

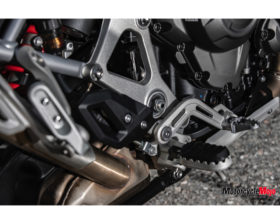

Wheelbase is 40 mm longer, at 1,560 mm, and there’s now a dual-sided swingarm. Despite this, wheel removal seems easy, requiring the removal of the axle and a triangular portion of the swingarm that’s held on by two bolts. To provide further clearance for that 21-incher, a pair of side-mounted radiators have been put in place of the single centrally located rad. While they might be prone to crash damage, they don’t really come close to the ground in a tip-over, and you can install accessory crash bars (standard on the Rally Explorer) for added security.

Semi-active Suspension

Showa provides the 49 mm inverted fork and single shock. The suspension is semi-active on all models, and it is electronically adjustable for damping through the bike’s TFT instrument panel. When you select a suspension setting through the menus, you’re simultaneously adjusting the compression and rebound damping at both ends. There are nine levels of adjustment, though road and off-road modes have dedicated damping forces for each level.

Also, sensors monitor when the bike is in the air, and the suspension firms up automatically for the landing. Rear preload adjusts automatically to maintain ride height based on load (the preload servomotor is mounted to the left of the subframe). The drawback of this system is that you can’t adjust rear ride height separately if you want to quicken steering, though after spending time on the different models, I found no need to.

Claimed wet weight varies between 240 and 261 kg which, depending on the model, is up to 25 kg lighter than before. That’s a huge weight loss, and Triumph says the new Tiger is up to 17 kg lighter than a comparably equipped GS. Aside from the lighter frame, other components have also lost weight, including the engine, swingarm, and the gas tank, which is now made of aluminum.

Another change was to go from a rubber-damped drive shaft to a solid one, which reduces unsprung weight and provides a more direct connection between the engine and rear wheel. The trade-off, however, is harshness on throttle transitions, mostly noticeable mid-turn on pavement or when making sloppy gear changes. A cush drive in the drive unit absorbs some of the drive-line snap, and this harshness almost disappears on dirt, where the absence of grip provides additional damping.

Hitting the Pavement

The first day was spent entirely on asphalt: 290-km loop of twisty, undulating mountain roads split between the GT Explorer and the Rally Explorer. When seated, the two bikes feel different even at a standstill. The road-oriented GT has a more nose-down pitch and feels lighter and lower than the Rally. While both bikes are tall, the Rally is tippy-toe tall — and I’m a six-footer. The bike is narrow between the legs, though, which makes reaching the ground easier.

The first day was spent entirely on asphalt: 290-km loop of twisty, undulating mountain roads split between the GT Explorer and the Rally Explorer. When seated, the two bikes feel different even at a standstill. The road-oriented GT has a more nose-down pitch and feels lighter and lower than the Rally. While both bikes are tall, the Rally is tippy-toe tall — and I’m a six-footer. The bike is narrow between the legs, though, which makes reaching the ground easier.

There’s ample legroom, even with the seat in the lower of two positions, and you can set the seat height without any tools. The handlebar is taller on the Rally, and the risers are in different positions depending on the size of the gas tank; the Explorer models have risers mounted about an inch forward to clear the tank. It looks like you can alter the position of the risers, but we were told that they cannot be adjusted. The windscreen is adjustable over 60 mm by simply lifting or lowering it with one hand. The seat is wide, flat, and proved comfortable after several hours on the road.

Seat of the Pants Impression

The weather was cool in the morning, so I turned on the seat and grip heat. The first thing I noticed after rolling away is that first gear is tall, requiring a bit of clutch slippage to get going, though the engine’s massive torque prevents stalling. The seat of my pants tells me that the BMW GS has a slight edge in power delivery from a stop, but the Triumph will walk away from it as soon as its tach passes 4,000 rpm — keep the engine spinning above that and it pulls like a powerful sport bike.

Lifting the windscreen to its highest position cut the chilly morning windblast to my torso, but it also induced a fair amount of helmet buffeting, which was amplified by my helmet peak. The sweet spot was about halfway up, which reduced buffeting to a comfortable level while still providing adequate wind protection.

The six-speed gearbox is feathery light when using the clutch, though it firms up slightly if you use the quick shifter. The Tiger 1200 is the first bike I’ve ridden on where the quick shifter could be used comfortably even at low speeds. Other bikes’ quick shifters are often clunky and high on shifter effort at low speeds, causing me to resort to clutch use around town; on the Tiger, it remained light and almost seamless in operation.

Steering is light and neutral, and despite the wide handlebar, the bike is stable and free of weaving in a straight line at high speed. It rails through sweepers and successive turning transitions with relative ease —

relative because the bike is tall, and it’s a long way up from a lean and back down again. You must, nonetheless, adapt your riding style to keep a fast pace on winding roads, since the Tiger isn’t conducive to a hard-charging approach, but rather, rewards smooth braking — braking hard will soak up most of the fork travel. The only hitch in this otherwise stellar back-road carver is that driveline lash, which is sometimes noticeable in the lower gears through turns.

Blind Spot Warning System

Spending time on a pair of Explorer models allowed me to experience the new blind-spot warning system, and I found it to be very useful. It’s easy to scoff at certain rider aids, but when they don’t deter from the riding experience and improve safety, they’re a good thing. I always check my mirrors and blind spots, but have been caught off guard by errant drivers changing lanes unseen behind me.

This system warns you when there’s a vehicle in close proximity behind you by illuminating a bright yellow light below each mirror. It works as claimed, the only drawback being that, if you ride in a tight staggered formation with your buddies, the warning light stays on. Also, I didn’t use it at night, so I don’t know if the bright warning light is a hindrance. However, if you find the system annoying, you can turn it off. I did not find it annoying.

Switching to a Rally Explorer in the afternoon revealed a bike that felt taller and slower through esses, and tended to run wide occasionally at corner exit due to its more relaxed geometry and 21-inch front wheel. Suspension compliance was also notably softer, though its wide range of adjustability allowed me to firm it up enough for a fast pace. The bike gave up little in the way of speed, however, and handily kept up with the GT ahead at a fast pace.

Hitting the Dirt

The next day’s ride was almost entirely on dirt, except for some short bits of connecting pavement. The route varied from fast fire roads to tight, undulating tracks, to some tighter enduro trails, with a touch of single-track thrown in. Most of the surface was hard packed, much of it was rocky, some of it was sandy, and there were ruts, water crossings, and steep climbs and descents to keep you on your toes.

Here, the Tiger 1200 Rally Pro really impressed. We immediately set a fast, elbows-up pace, and after a while I found the sweet spot in the ride mode and suspension settings. From the get-go I selected Off-road mode, which raises ABS intervention at the front wheel, turns it off at the rear, loosens up traction control enough to break the rear loose at will, sets the suspension to standard (for off-road), and sets throttle response between the most aggressive Sport mode, and the less aggressive Road mode. You can also set the throttle map to Rain, which provides the softest throttle response and limits output to 100 hp.

I eventually tailored the setup by setting the suspension damping one step firmer than standard, selecting the Road throttle map for slightly softer response, and switching off the traction control to be able to climb the steep, sandy ascents. You can leave various menus up on the screen and make changes on the fly, as I did this for the suspension, using the joystick control on the left switch assembly to adjust it as I rode. Due to legislation regarding ABS, the bike will default to Road mode every time you turn it back on. However, if you shut off the bike while in Off-road mode, a message pops up on the screen upon start-up to remind you to confirm that you do, indeed, want to remain in Off-road mode. It’s a handy shortcut that bypasses having to scroll through menus to do so.

Stable in the Rough Stuff

With my preferred settings selected, I really gelled with the Rally Pro, riding confidently at a fast pace despite dusty conditions that reduced reaction time. The suspension proved to be excellent. While the Rally Pro is agile enough to react quickly to obstacles, the dust meant I sometimes came up suddenly on deep ruts or big rocks, fully expecting to get hammered by the impact. Yet, the bike soaked up the rough terrain without bottoming, and only wavered a bit offline if it hit a really big impact. A lot of this is due to what Triumph calls a “virtual spring rate:” While the fork and shock use straight spring rates, sensors monitor when travel is used up quickly, and damping is immediately firmed up to help absorb the shock.

With my preferred settings selected, I really gelled with the Rally Pro, riding confidently at a fast pace despite dusty conditions that reduced reaction time. The suspension proved to be excellent. While the Rally Pro is agile enough to react quickly to obstacles, the dust meant I sometimes came up suddenly on deep ruts or big rocks, fully expecting to get hammered by the impact. Yet, the bike soaked up the rough terrain without bottoming, and only wavered a bit offline if it hit a really big impact. A lot of this is due to what Triumph calls a “virtual spring rate:” While the fork and shock use straight spring rates, sensors monitor when travel is used up quickly, and damping is immediately firmed up to help absorb the shock.

The quick shifter continued to make the clutch almost redundant off road; I used it only to get going from a stop, or when the speeds were low enough that the tall first gear required some clutch slippage in tight corners.

The Question Remains

We were told during a pre-ride technical briefing that the new Triumph Tiger 1200 was designed to compete directly with the granddaddy of adventure-touring bikes, the BMW R1250GS. That’s a pretty bold target, since BMW essentially invented the category in 1980 with the R80 G/S and, after four decades of refinement, has set the bar quite high. While only a direct comparison with the big GS can settle that debate, I have spent a lot of time on the BMW and can say that the new Tiger 1200 Rally handles better off-road, is more forgiving if you make a mistake, and requires less effort to ride when charging hard.

It’s also easier to ride off-road for average to intermediate riders than the ready-to-race KTM 1290 Adventure R, which rewards expert riders at an expert pace. The Rally Pro in particular scores big for its excellent suspension, off-road friendly wheel sizes (like on the KTM 1290 Adventure R), and a low-maintenance shaft (like on the BMW R1250GS). It gives up little in the way of road performance to the GT, weighs less than the Rally Explorer, and actually feels more like a middleweight adventure bike than a big-bore 1200. Add it all up and Triumph has a winner.